“There should have been a succession of national elections in Angola, Mozambique and Guinea, but by the time that Lisbon had delegated authority to the newly-emerged countries, all three had embraced hardline Marxist principles.

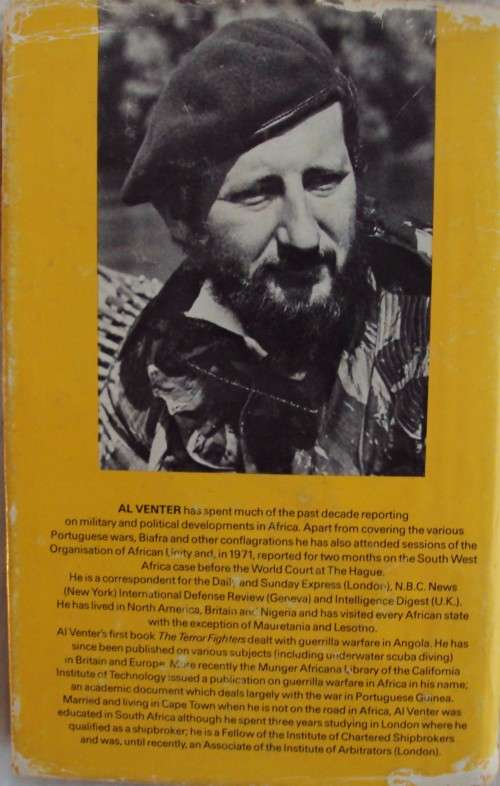

By the early 1970s this not only implied merely a growing percentage of locally recruited or black individuals incorporated in the regular forces fighting the nationalists, – in the same sense as the French jeunissement in Indochina – it now meant a process of creating and fostering combat units of Africans operating more or less irregularly and autonomously, and with high levels of operational efficiency. “Africans were increasingly brought into the administration of the territories and the changes that occurred at this point brought a new meaning to the concept of Africanisation. “…when the dust eventually settled and moderate minds were able to look at all these issues dispassionately, one of the first conclusions reached was that as in the Rhodesian and South African wars – slowly gathering their own momentum once the Portuguese had returned to Europe – the bulk of the people of all those countries tended to side with their own. At the time Portugal was the second poorest state in Europe, but was resolute in maintaining its hold over Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau.ĭistinct from Mozambique the Portuguese counterinsurgency operations employed in Angola, and Guinea-Bissau were militarily successful, but fiscally calamitous for the Portuguese state, and acted as a prime mover for the Carnation Revolution which brought about Portugal’s ultimate withdrawal from Africa. The Portuguese encountered well funded, and amply equipped nationalist insurgencies sponsored by both the Soviet Union as well as China. Venter recounts the Portuguese counterinsurgency campaign conducted in their colonial possessions of Africa from 1961 to 1974. In his book Portugal’s Guerrilla Wars in Africa, wartime journalist Al J.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)